Practical Object-Oriented Design, by Sandi Metz, is a book 📖 I recently read. In the book Ruby was merely just a tool to explain the concepts of designing a program in OOP. The book went through some iterative thought process of how one would approach writing ‘changeable code’ - one that is adaptable for future changes and reduce cost of maintainance.

I wanted this post to be a pictorial collection of my notes about some difficult concepts. Some of which might be applicable in the near future. But by no means is this a full summary.

Single Responsibility

- Class and methods should do ☝️ thing. You should be able to summarize the method/class’s purpose in one sentence. Small methods are easier to maintain, is more obvious, and reusable.

- Depend on behavior not data. Don’t access data directly, but wrap it in a method or struct. In Ruby one could add a getter/setter method by using ‘attraccessor’/‘attrreader’/‘attr_writer’.

Managing Dependency

- Dependency: is the need to know other class’s name, method, arguments, order of arguments. A change in a class requires change in its dependents. This is costly.

- The direction of dependency could go in either direction. As a rule of thumb, always depend on more stable things (won’t change often). I’d imagine a dependency tree where the root is more stable then it’s children/dependents. E.g. abstract class is more stable than concrete class. Concrete class therefore shouldn’t have many dependents (other class calling it).

- Postpone decisions until you have enough context. You can temporarily isolate the dependencies so it can be refactored later. Dependency are foreign invaders. Make sure to explicitly expose them (ie. isolate them in a method)

- prefer keyword arguments

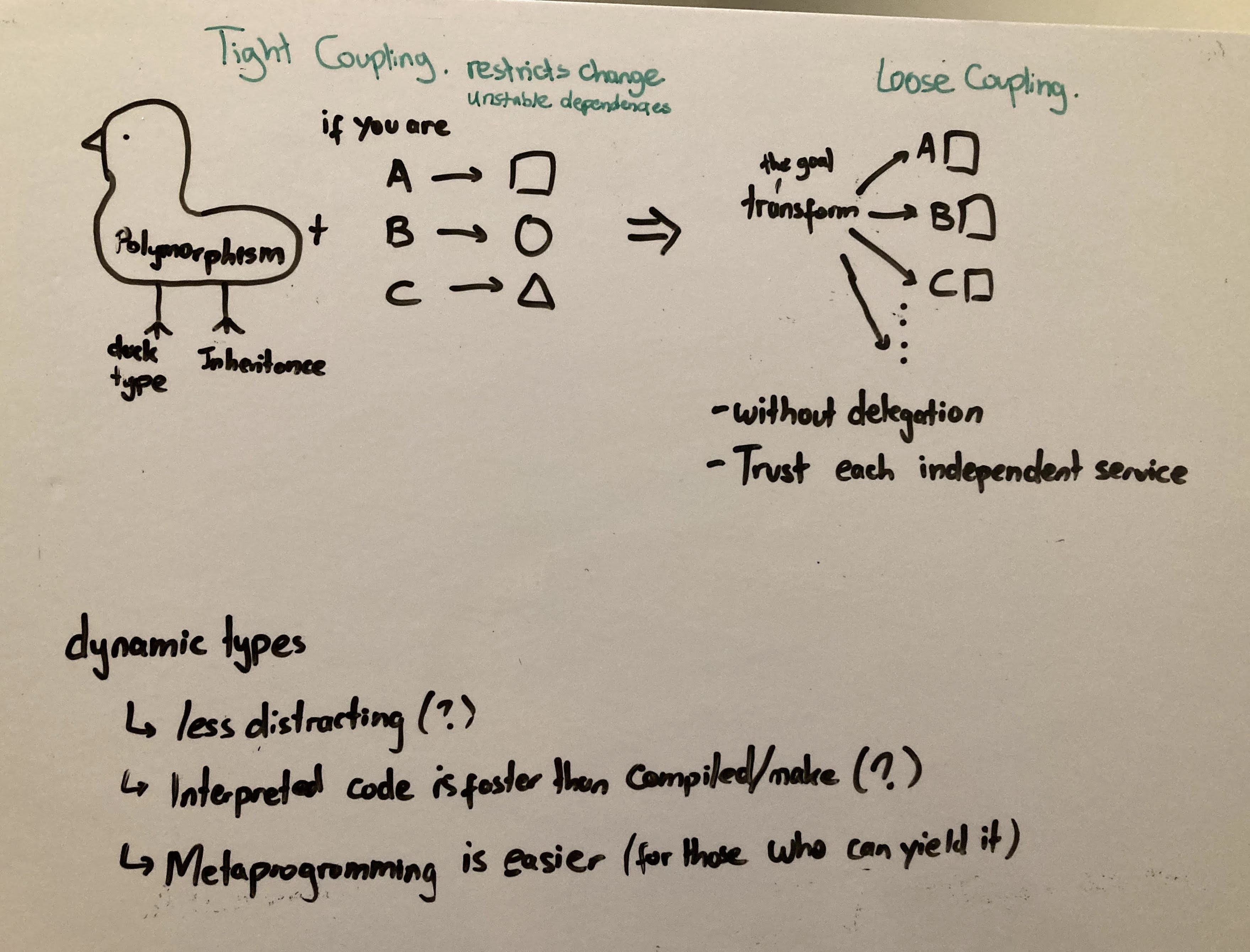

function(x:, y:, z:), so arg can be passed in any order. - Use polymorphism to avoid delegation. Rather than ‘check if object is A do this, if object is B do that’ -> you could use polymorphism (i.e. duck typing or inheritance) so A and B implements the message you’re trying to call. The caller now trusts that each object is the right type and simply call the message (without knowing/depending on each target class).

- There’s some notes on why dynamic type language like Ruby is an advantage. Personally not too convinced now; but I’m hoping this will change.

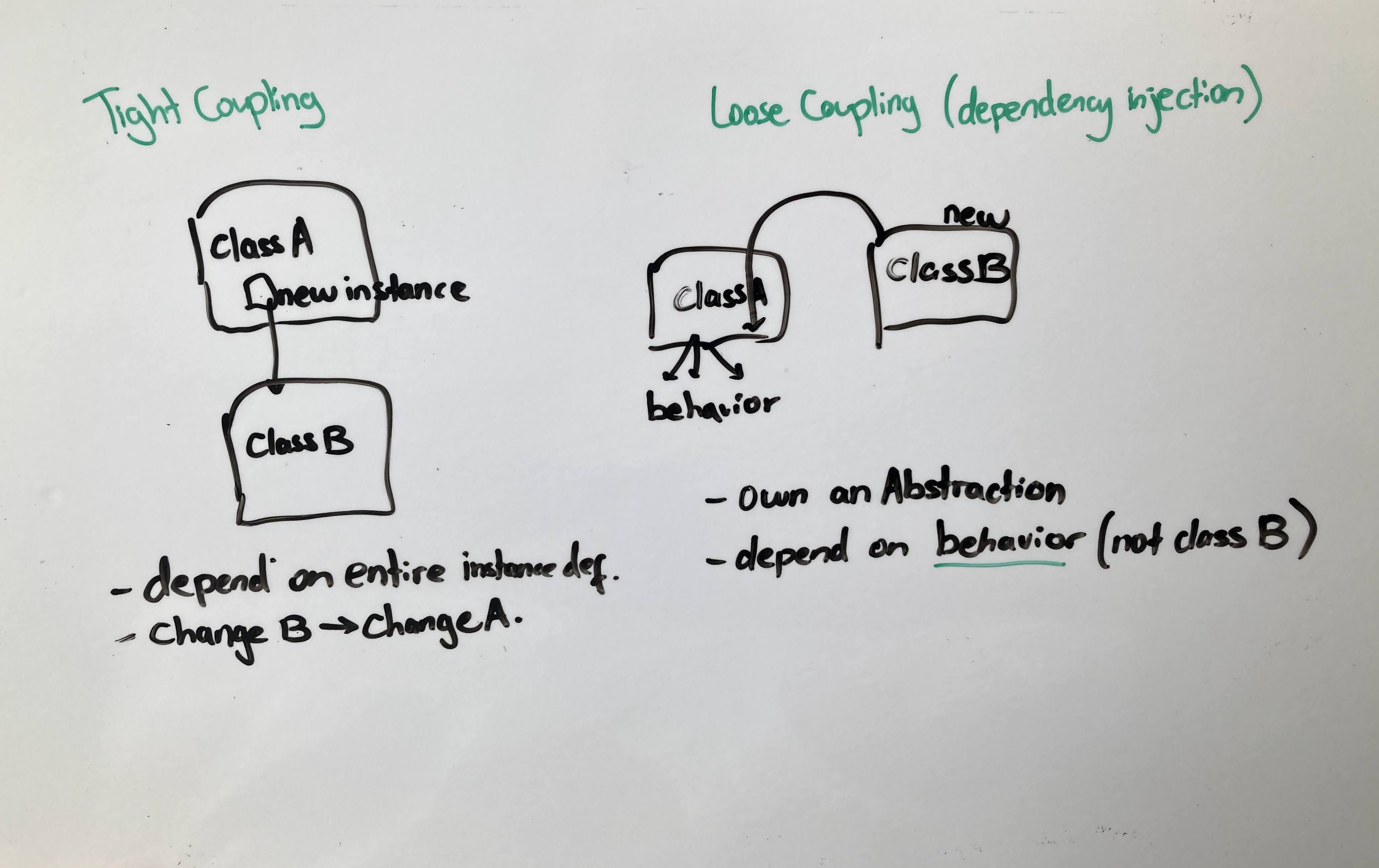

- Dependency Injection: the class should depend on behavior, not the type of instance. Loose coupling is achieved by initiating the object outside, and inserting the ‘behavior’.

- Dependency Injection: the class should depend on behavior, not the type of instance. Loose coupling is achieved by initiating the object outside, and inserting the ‘behavior’.

Flexible Interface

- public interface (public methods) is contract, that should be stable.

- Sequence diagram: helps you focus on message-based design (“I need to send this message. Who should respond to it?”). Think of the message before the object.

- Analogy: Tell the chef what you want. Without specifying the ingredients/recipe.

- similarly, a ‘Trip’ class shouldn’t define the procedure (ie. do this do that), nor should it contain the context of other classes (ie. preparebicycle). It should focus on what it wants (ie. a Trip wants to be ‘prepared’. The preparer is abstract and can be any object that implement the duck type ‘preparetrip(self)’).

- Make interface explicit.

- Private: must be called by implicit receiver (e.g. self)

- Protected: allow implicit receiver & explicit receiver that is of same type or subtype.

- Public: stable and visible anywhere

- Law of Demeter: long chains (classA.classB.classC.d()) indicate that public interfaces are lacking.

- Duck types are public interface that’s not tied to particular class. They share code via modules (more on this later…) Test is the best documentation. (more on shared test later…)

Inheritance

- Inheritance: is the delegation of unknown calls to its uperclass.

- ‘super’ in Ruby, calls the superclass method (with the same method name). If no argument specified, by default the overrided pass all its arguments to superclass.

- Abstract class is a repo of common behavior. Can’t be instantiated.

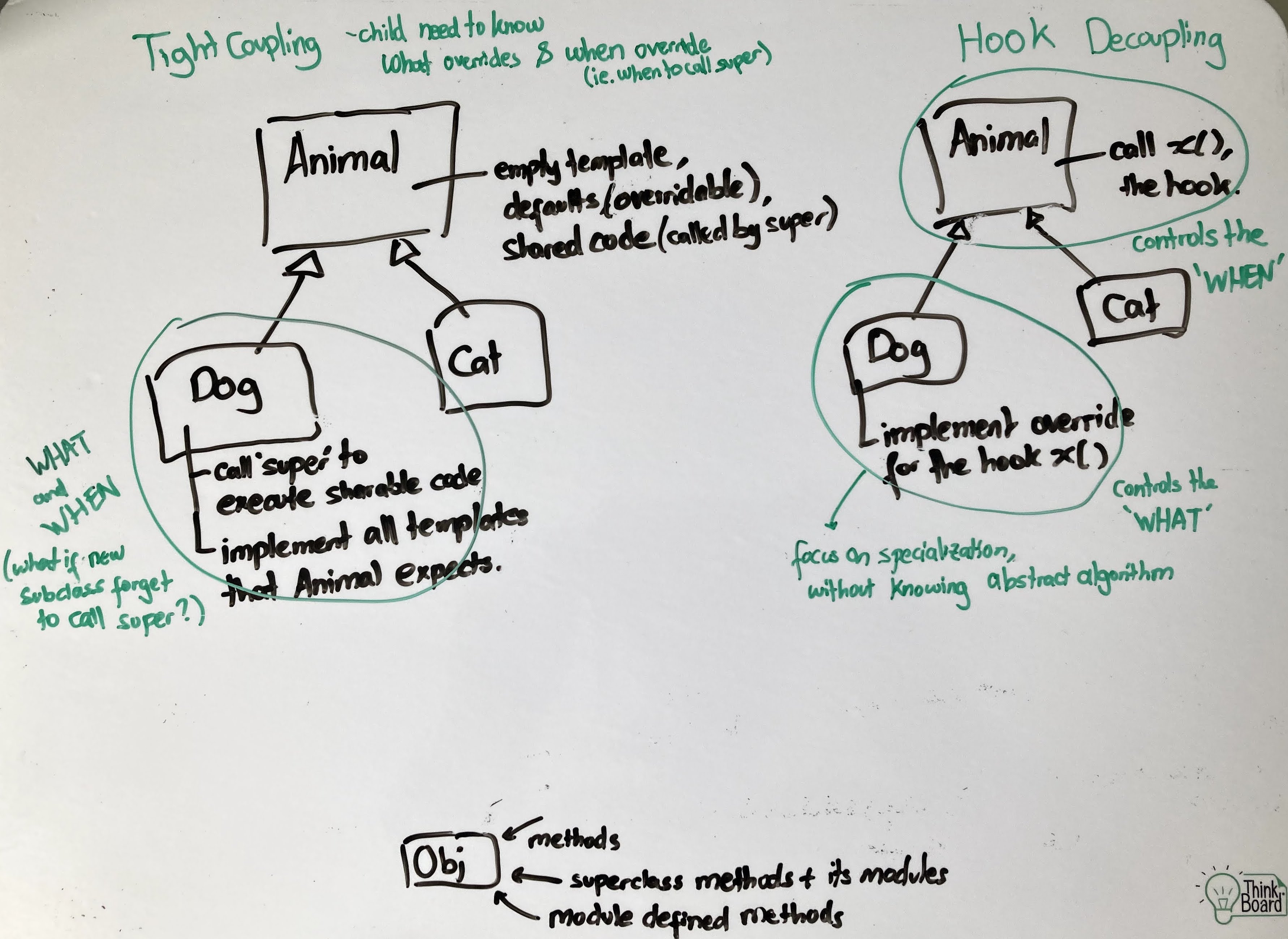

- Template method pattern: superclass sends the messages to its subclass to acquire the specializations of it’s subclass. Superclass must define fallback method (a template - a HOOK) if the subclass doesn’t implement it.

- the oposite of calling ‘super’ (calling super requires subclass to know superclass’s implementation, which is bad / tight-coupling)

- thus, subclass don’t have to know how to interact with superclass.

Modules

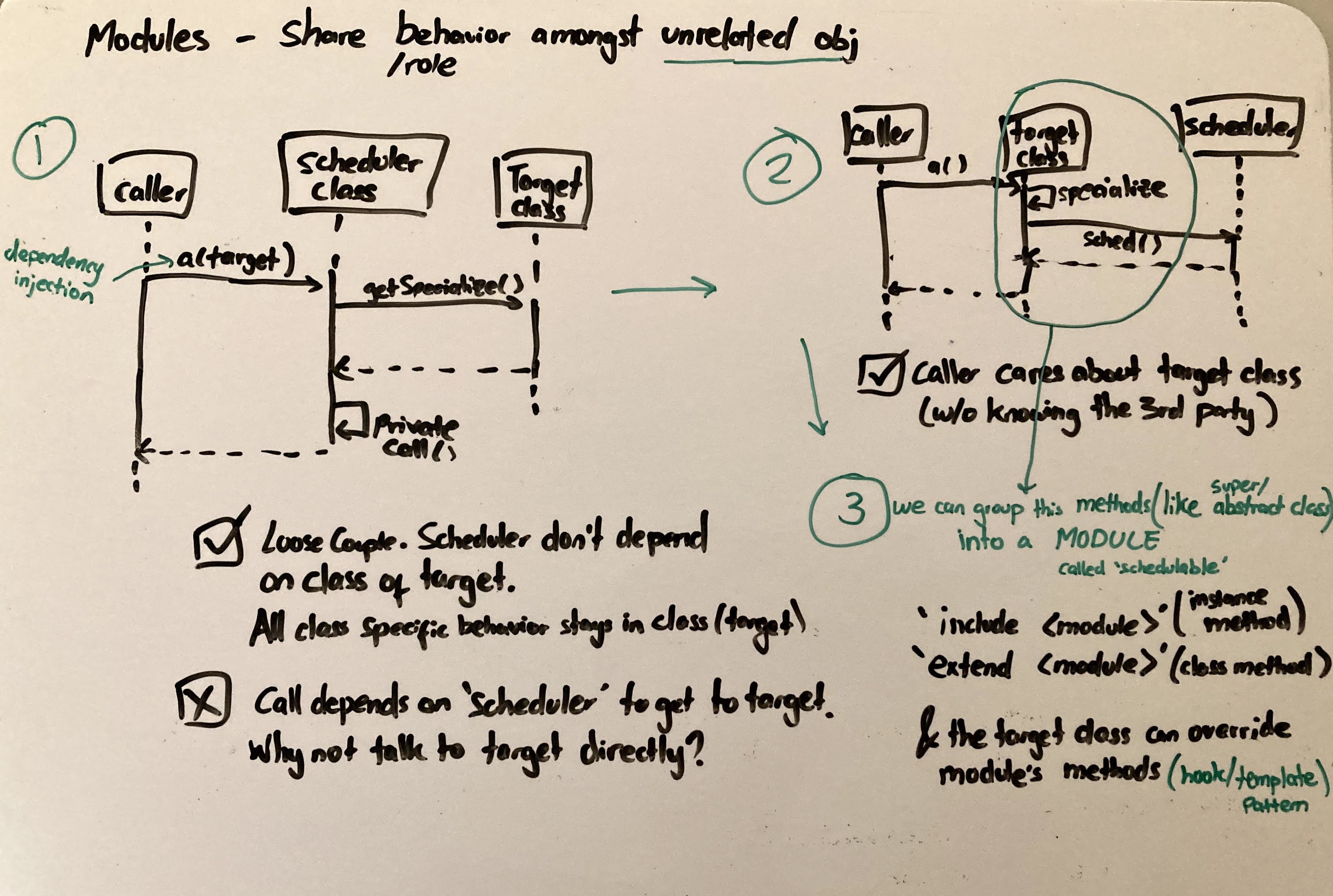

- Modules: allow different object types to play common role (ie. schedulable and scheduler). Is also a way of automatic delegation just like Inheritance (but for unrelated types).

- in Ruby, ‘include’ modules adds it to the instance of a class (instance.x). ‘extend’ modules adds it to the class (Class.x).

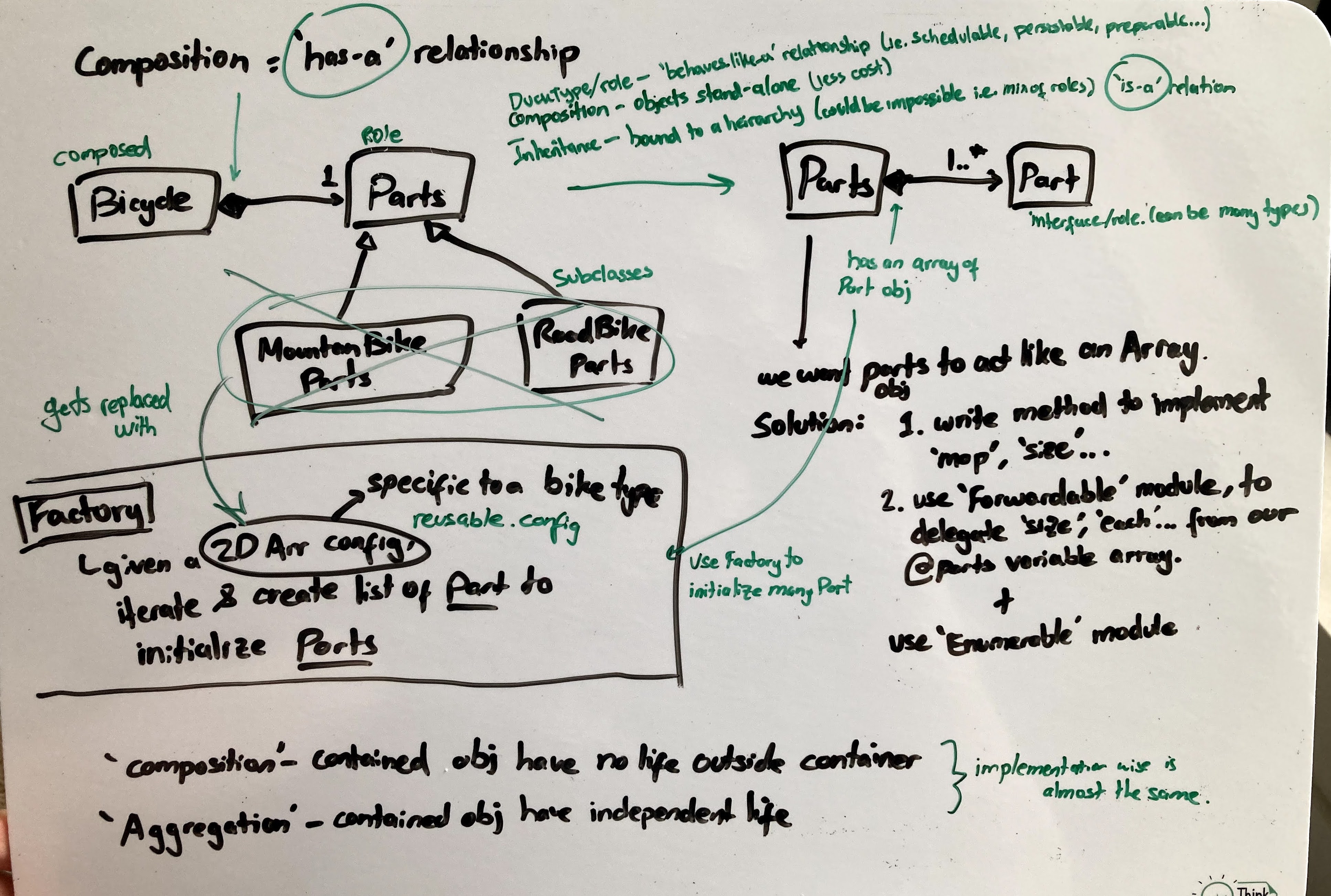

Composition

- Larger object owns (has-a relationship) other objects.

- Factory: is object whose purpose is to create other objects.

- Aggregation: is like Composition, except that contained object has ‘independent life’ to it’s container. (e.g. Parts object contains an array of Part object).

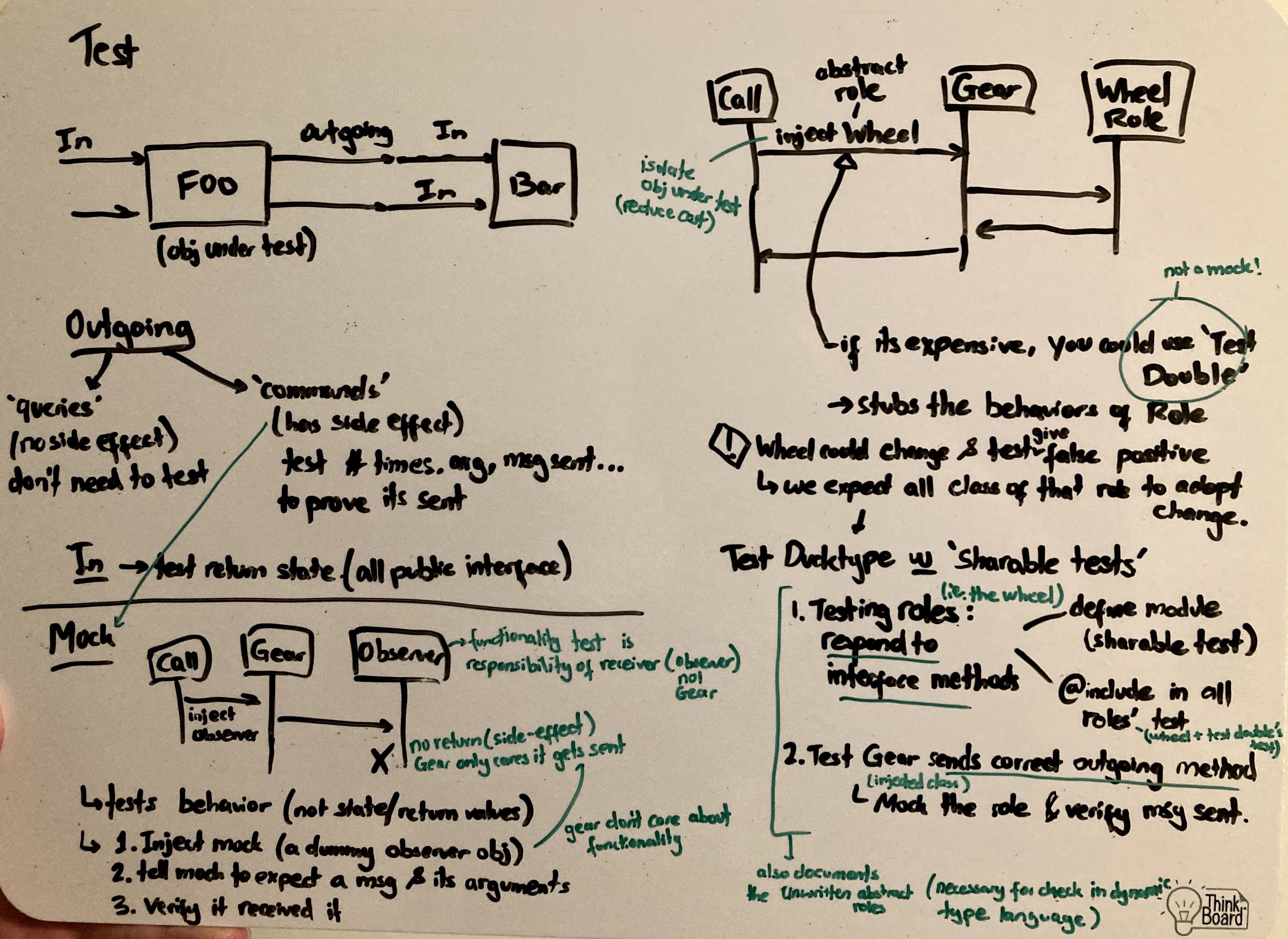

Test

- Test gives you confidence to refactor constantly (change design decision without altering external behavior).

- Tips

- It’s annoying, but the solution is to get better at it (not stop testing).

- write test as if you expect your future self to have amnesia.

- a hard-to-write test is a sign of too much dependencies / hard to reuse

- Don’t write private methods, but if you do, never ever test them.

- Only test public class

- Test incoming message: test of state (make assertion about return values)

- Testing the 2 types of outgoing message.

- Commands - has side-effect (eg. file I/O, DB). It is the sender’s responsibility to prove that it’s properly sent. Is a test of behavior.

- assert # times and with what arguments the message is sent.

- Use a Mock! (a dummy observer object that expects a message & arguments)

- Queries - has no side-effect. Don’t require any test

- Commands - has side-effect (eg. file I/O, DB). It is the sender’s responsibility to prove that it’s properly sent. Is a test of behavior.

- Testing an expensive role

- Use Stubs / Test Double!

- Stub is a dummy object that implements the same interface. However, what if the role changes? then the test double is forced to change. How is this enforced (to prevent obsolete stub - false positive)?

- Use shareable tests! (a test module class) Easy way to test every object that plays the role

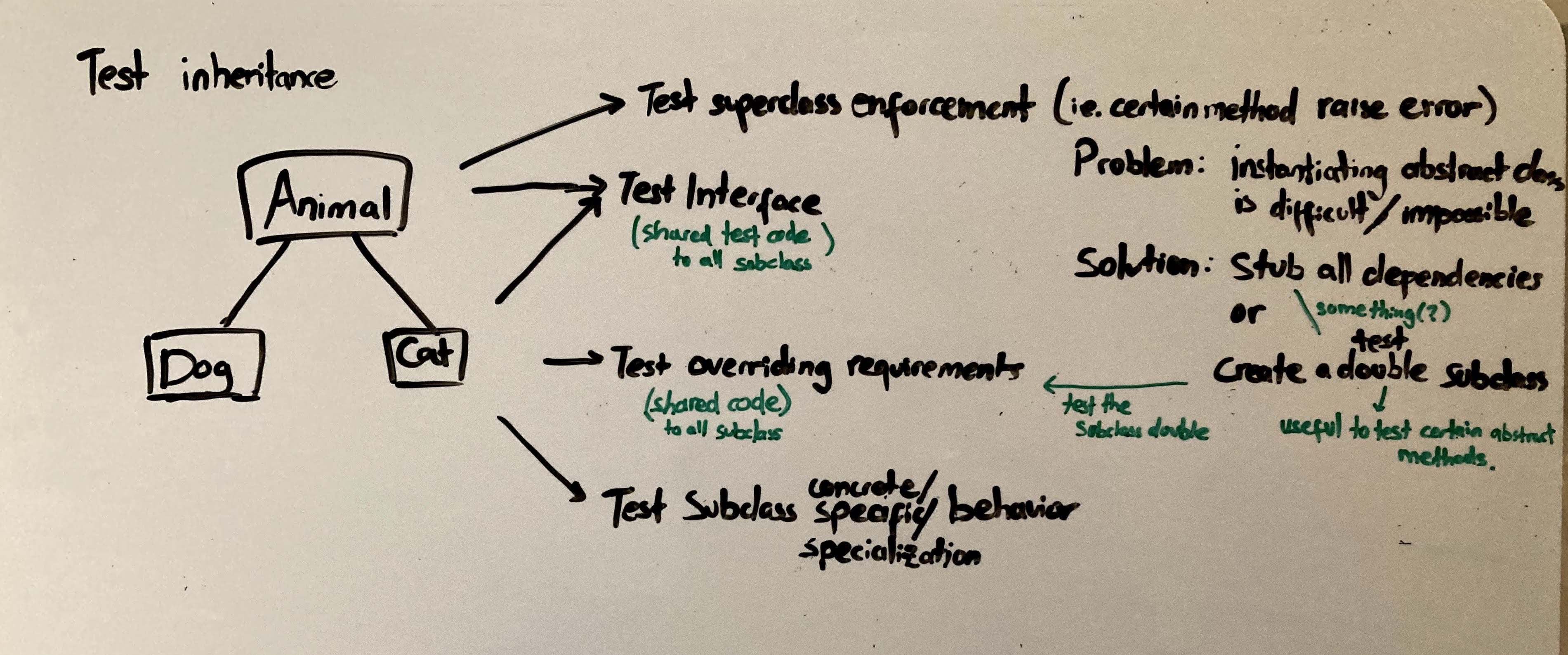

Testing Inheritance

- Similarly, one could test the superclass interface using sharable test modules.

- Generally, you shouldn’t instantiate abstract class, but you could do it in the test. This might not work for all abstract class. In that case, stub the behavior of subclass.

- You could define shared module (ie. AnimalInterfaceTest) to test each subclass that they responds_to the shared public abstract methods.

- You could define shared module (ie. AnimalSubclassTest) to test each subclass that they responds_to the required abstract methods to override (note: if not overriden, the abstract class should throw error).

And that is all!

Learned stuff that seems pretty important but is often ignored. Lot’s of Aha! moments. I’m hoping reading this would help me be more conscious of design decisions in every code I touch.

I think it could get pretty awfully complicated, and probably needs a lot of iterations to get right. But it would certainly help to start thinking about it!